By Anne Pellicciotto

See more of Anne's work in her book.

The director of the Cultural Institute said people will stay home and watch television and drink beer, their usual Rioverde Friday night routine. ‘Falta de education, ni modo,’ what can you do, he shrugged his shoulders. ‘Get a small cake,’ he advised.

But I didn’t listen. I got a huge cake; and the people did not stay home.

The Semillas of Esperanza turned out in numbers, in their high heels and flowing vestidas, niños in tow with gelled hair and polite gallery comportment. The owner of Yogurlandia, my landlord and her daughters. Antonio the artist was there and Samantha the librarian and a doctor I’d never met who came to record the event on the new Ipad!

I’d done my homework, distributing flyers all around town, from the Mayor’s office to neighbors’ homes to the shops around the Centro and to strangers in the main square. 50th Aniversario de Peace Corps en Fotografía: Exhibición y Celebración.

I’d learned over the years with my photography: it’s not just about the shooting, nor the sorting and selecting, processing and printing. I fought for three hours last Friday night with the Spanish-speaking Kodak machine in Galvan’s shop. I misinterpreted some prompts and had to restart my portfolio of edits from scratch twice!

50th Aniversario de Peace Corps en Fotografía: Exhibición y Celebración

In the end the prints turned out beautifully, the colors popping off the page, the cropping exactly to spec. But it was not enough to have the perfect collection on the walls if no one came to see it.

As the guests filed into the courtyard, taking seats in familial clumps, I scrambled around the gallery with title tags trying to find their mates and shoring up photos slipping from the walls in the 100-degree heat. We were so close. But what really had me perspiring in my black party dress was the formal panel table and microphones they had setup in the courtyard. The Regiadora and Director were waiting for me to take my place at the head table and give a speech.

‘Can’t the art just speak for itself?’ I wondered aloud as I jammed bottles of white wine into the cooler of ice.

Kuko overheard me and understood. A painter himself and assistant at the IMAC, he’d also taken on the role of cultural interpreter through the exposition setup process. ‘It’s the way we do it, Anna,’ he clarified, shrugging. ‘Official process. All the openings go like this.’

‘Por supuesto, Kuko’ of course. I appreciated the cross-cultural nuances and the Mexican fondness for ritual. I was just nervous – and unprepared.

The final photo tag hung, the registration table setup, the wine on ice, we took a step back to gaze at the gallery, the amber light, the regal cake ready to be sliced, the space in beautiful, calm order after days, weeks of preparation.

‘Listo,’ Kiko and I agreed, exhaling in unison.

I brushed off my dress, took a deep breath, and entered the courtyard. Gazing out at an audience of smiling faces, in this sudden quiet moment under the stars, I remembered what I was going to say.

Promover la paz y amistad mundial.‘ Promoting peace and friendship is something that photography can do,’ I explained, ‘creating a dialogue that goes beyond words.’ And I invited the guests, as they toured the gallery, to share their reactions, questions, impressions to my perspectives of their pueblo.

After some light applause we filed toward the gallery behind the officials who carried three pairs of scissors on a red velvet pillow. Pausing at the door before the giant orange ribbon, we picked up the scissors and, in unison, cut the ribbon, officially opening the festivities and making way for the guests to enter.

Within moments the gallery was full of energy and animated conversation. I watched the hairdresser’s sons staring at themselves in my Palm Sunday procession photo and Alicia, with her fishbone braid and dimples, peering into open walls of the abandoned Planta, while a regally dressed senora lifted her spectacles to get a closer look at Sombreros Escuchando, Hats Listening. Samantha’s favorite was Niña Volando, Flying Girl; and Kuko liked Montaña de Maiz, Corn Mountain. ‘An interesting way to look at it’ he said.

We drank warm wine and ate stale sandwiches and all the while snapping more photos for posterity – photos of photos and all of us in front of the photos, around the urns, the chorus line of women from Puente de Carmen, new amigos and acquaintances. We made a toast and reluctantly cut into the beautiful cake, made by Sophia, a piece of art itself, decorated with the Mexican and American flags, merged, red, white, blue and green and oozing with chocolate, strawberries and cream.

Then suddenly, in typical Mexican style, we were all informed we must leave. The funcionarios had removed the food from the table and shut-down the music. It was 9 pm; there was no guard on duty, so apparently they had to close. Of course there hadn’t been a guard there all day – Cesar had not shown up for work. Daniel and the ladies in the office were simply ready to go home. But they could not get the conversations to stop and the people out the door; so they gave-up and just left us there to continue our celebrating and finish off the last of the wine.

As the crowd dwindled down to just a few of us, the diehards, we started getting silly, hanging out the barred windows of the former prison building, pleading for freedom, snapping more photos for posterity. Eventually we closed and locked the massive wood prison doors behind us, then wandered the streets giving out leftover cake.

A few days later, after all the excitement had died down and Peace Corps life was re-normalizing, I was walking the sweltering streets of Rioverde and feeling the slightest bit of post-show letdown. None of my co-workers at SEMARNAT or the Municipio had shown-up, and I wondered why. Was all the effort and expense really worth it? And what does art matter anyway, in the work of development?

Ni modo. I was already onto the next thing, meeting with the judge about our EcoFeria plan. Rushing past the storefronts on Madero, heads-down, going my usual Americana pace, I heard my name.

‘Anna, podria hablar contigo?’ the pharmaciast called out, his hands cupped around his mouth.

Darn. I reluctantly crossed over the narrow street and ducked beneath the scalloped awning. ‘Mande, senor?’ I asked, glancing at my watch. I often stopped for a Gatorade and a chat; but today I really didn’t have the time.

‘Victor,’ he corrected me, smiling and nodding. Then he delivered a profuse and heart-felt apology for missing the photo show on Friday, explaining something about a sick family member, out in Pastora, mil disculpas.

‘No problema,’ I responded, explaining that he could visit anytime over the next two weeks. The photos will be up.

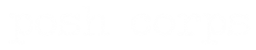

‘Ya! I already did, on Sunday with my family,’ he said. His eyes lit-up as he explained: his wife Celia loved Birds on a Wire, and his son Benjimin loved the Flying Nina. But his personal favorites were La Planta and Corn Man. He buys his elotes from Serapio, too, they are the best. And it’s such a good funny of him. Just like he is.

‘Muchas gracias,’ I said, grateful for but a bit uncomfortable with such praise.

Victor continued, the words gushing, and I tried to catch them as best I could. His son speaks a little English; he’s learning. It’s so important to know another language, don’t you think? Would I be willing to talk with him someday, to help him?

‘Claro, como no, sure why not?’

Then he told me this: He hadn’t really understood why I was here in Mexico, in his little town; and now, after looking at my photos, he did. Then he came from behind his counter in his white pharmacist coat and, contrary to distant Rioverdense style, he gave me a hug.

‘Thank you for being here in our pueblo,’ he said, ‘for leaving your country to do this work for us. Muchimas gracias, Anna.’

I felt my face redden. I didn’t recall anyone thanking me before. It felt odd, nice, bittersweet. As much as I tried to suck them back, a few tears forced their way out. I didn’t want the pharmacist to see so I ducked out quickly, thanking him and waving as I continued down Madero.

I noticed my pace slow and the heat subside the slightest, remembering that I may never know the impact I’m having. All I could do was plant some seeds; and with some water and light and luck, they might one day become trees.And then there was the impact they had on me.

- Anne Pellicciotto served as a Peace Corps Volunteer in Mexico from 2010 through 2012 in the pueblo of Rioverde, San Luis Potosi. This piece is an excerpt from her book in progress, Stories from South of the Border on Surviving, Thriving and Serving.